Season 2008: The below article was first published on former web pages and is reprinted here as I wrote it. Some updates have been added as indicated and original photos may have been replaced with different photos which were taken at the time. The “Smithonian specimen” remains as one of the finest from the district and is unrepaired. At the time of its discovery, it was the finest unrepaired specimen known. (This article will be moved into the time line after I post another of the earlier articles.)

Season 2008

We invested 34 days operating heavy equipment on the Smoky Hawk at Site B during 2008, the same site we had been working for the past three seasons. This represented over 60 percent of our planned operations.

We first opened Site B in 2005 using a John Deere 200. Because we discovered a rich structure with numerous pockets, I went ahead and re-permitted to extend the disturbance area up the slope and to the northwest. By 2006 this was approved and we re-excavated Site B, expanding upslope. By end of 2006 it was clear there were several bands of pegmatites, so during 2007, we continued uphill. Most of the pockets were recovered from the southeast, south, and southwest portions. Unfortunately, we hit hard rock at the end of the 2007 season in this area and the areas to the north and northeast were completely barren. We considered “pulling the plug” on the Smoky Hawk considering the difficult hard rock we had encountered.

Nevertheless, we began discussing deepening the excavation to determine if there were deeper pegmatites in the unaltered granite. To this point, our mining had been restricted to the decomposed granite and some rock we could break with the hydraulic hammer. If we intended to go deeper, we would need to blast. This required changing the permit to include blasting at this site, so I spent the winter of 2007 and spring of 2008 preparing for blasting.

On 9 June 2008, we began site preparation. We brought in the 690 loader to help move overburden off the site. By 11 June, we had cleared the working site, exposing a knob of unaltered granite on the left side of the excavation. We began by drilling four holes about eight feet deep, loaded the holes, and shot them. This cracked the knob, but the pieces were too large to move. After the second round of blasting, we were able to clear out the rubble. No pegmatites showed within this structure.

Behind the knob, along a more decomposed section of granite, we did hit a couple of small pockets. These were on the far right side of the excavation and opened along a pegmatite which ran across the excavation. A third pocket was discovered a few days about 10 feet along the pegmatite. This pocket produced one outstanding, intact plate. The pegmatite soon dove deeper and again was blocked by unaltered granite, which were the remains of the granite knob.

Although it was 14 June, the weather was now unbearably hot. We began in snow less than a month earlier. We suffered two wind storms, one which ripped my canopy to shreds and bent the frame into a useless twisted wreck. We had also been hit by several severe thunderstorms. Fortunately, the timing of the storms had been such that we had only lost a few hours of operations. But this day, the heat made it nearly impossible to work.

It appeared the pegmatite we were working would extend to the northeast; however there was now 40 feet of overburden above us. We could not proceed without investing two more days with the 690 and the 992 removing the overburden and benching the high walls.

Week 6: 16 June through 22 June 2008.

Broke the rear axel on the truck trying to haul the water buffalo. Robert and George worked on pulling it apart and I worked on trying to locate the parts. After nearly half a day, I elected to have it towed in to Colorado Springs to my own mechanic. He got to it immediately.

Chuck Borland arrived Monday night. He will be helping mine the pockets now that we are back into some.

On Tuesday, Robert and George switched the diesel tank and equipment to the other work truck while the main truck was repaired. I arrived on site about 8 AM. A few friends had dropped in from Minnesota to visit and watch the operation.

Today (17 June) we worked the right side of the excavation, clearing off more from the floor and pulling out several of the large boulders. I worried the 992 couldn’t haul them out. One, we had to dig a hole in front of it and roll it in. We couldn’t lift it and didn’t want to drill and shoot it.

We have removed enough rock that we can continue to follow the pegmatite which has now produced pockets 08-020 through 08-022. Almost immediately we hit another long, skinny pocket, the color being a little lighter, but extending to the left, running up under some hard caprock. I used the chipping hammer to remove the surrounding rock and George and I pulled out some nice plates from 08-023. This pocket eventually ran for 5 feet in length and opened about a foot in height and depth. Although the color is light, it looks like we will get some great plates from it when it’s finally prepped.

My friend Jim Reed and his 11-year-old son Nick, helped us dig the pocket. They also found a smaller pocket, which appears to be an offshoot of the pegmatite, and pulled a really nice specimen from it. It was an unrepaired small cab specimen with several small amazonites at the base of a cluster of slender, two inch smokies. Nick sure looked proud holding up that specimen! (It’s now in his collection.)

Wed 18 June 08: The truck is finished so I picked it up last night. I’ll drive it out and Tim will bring out the blue Suburban, my mining truck.

Replaced teeth on the 992 today. We go through a set about every five days at a cost of almost $500.

Finished 08-023 today and hit another pocket, 08-024, immediately past it along the same pegmatite. This one had much better color. It also produced several manebach twins, but without smoky quartz. Jim and Nick helped us collect and wrap a few of these, but we decided to leave the remainder for scheduled visitors to see tomorrow.

I next used the bucket to remove the caprock off of 08-024. When doing so, it exposed the wall beyond it. We continued to worry out several more large boulders to further expose it. This is the section behind the knob that we had earlier drilled and blasted. Although we found no pegmatites in the knob, it had prevented us gaining access to this area. Now we nicked a large pegmatite. At it’s deepest part, we found a tiny pocket of incredibly blue amazonite. We then hit two more along the same pegmatite, 08-025 and 08-026. Unfortunately, most of the amazonites were crushed and there were almost no smokies. We may recover a dozen or so top quality amazonites, a whole bunch of cutting rough, and one or two smokies if we are lucky. The quality is unsurpassed however. If the pegmatite continues, it could produce a high-quality pocket.

Thursday 19 June 08: The weather again was hot and clear.

Today a group from the Colorado Springs Mineralogical Society visited along with Mike Wise from the Smithsonian.

We finished collecting 08-024. It produced a few more amazonites, but nothing of significance. The pegmatite also petered out. There could have been more; however, it would have been cut during earlier operations. In summary, this pegmatite produced five pockets, most of which had quality specimens.

I allowed the visitors to help with 08-024 and then work the pockets we had discovered along the newly exposed pegmatite, 08-025 and 08-026. We also discovered a side pocket 08-027, which appeared on a smaller, separate pegmatite. These were exciting looking pockets. Each showed a very heavy pegmatite rind, very reminiscent of the Dragon’s Mouth Pocket. As the visitors worked on these pockets, they quickly began finding a few nice amazonites.

After a short time, I had everyone step out so I could take off more of the wall to their left. When I did this, the continuation of the pegmatite was exposed. It descended from the surface, about a 45-degree dip. A small seam of incredible color began to show about 8 feet deep from the surface. This small structure did not trend with the dip of the main pegmatite but ran horizontal across the pegmatite.

Tim began working it and it soon began to open. It again appeared to be similar to the other pockets already found on this pegmatite—good color, but nothing but broken rubble. We collected it all, with the hopes there would be on or two single amazonites with single smokies. Both Tim and I were disappointed. The color was outstanding, but again, the pocket appeared to be a total shambles.

Tim had diligently removed about a foot deep of shards from the left side of the pocket before he found a couple euhedral amazonites. The sides of the pegmatite were also now taking shape. It had a distinct rind about 6 inches thick, all very good signs. He pulled out a few more fragments and suddenly, we were looking into a thin, but open cavity. Finally, some euhedral smoky quartz crystals began to show.

I brought the water into the hole and we began carefully washing the pocket. Smoky tip after smoky tip began appearing, rising from the pocket floor! We potentially had a good pocket.

At this point I grabbed the video camera and began taping. Our visitors, including Mike, had paused from their collecting efforts and were watching as Tim began finally pulling some good crystals out of the pocket. I remember announcing as I videotaped, “Well, here we are at the Smoky Hawk Mine where Tim has just opened up a terrific pocket. We’ve got club members from the Colorado Springs Club here and Mike Wise from the Smithsonian. Guess we’ll call this the Smithsonian pocket.”

I noticed Mike shaking his head. “I’m not sure about that.”

I continued taping, commenting on other aspects and documenting the pocket, similar to what we do for every significant pocket. It looked like this one could be significant.

We still had not recovered any groups. Tim pulled pieces from the pocket; club members wrapped. Chuck photographed and recorded. I ran the water to wash out debris and I labeled the boxes as we filled them with now, excellent singles. I suggested to Tim if he spotted any plates that he should allow one of our visitors to remove it. He replied, “I’ve been looking. There might be one along this side.” He pointed to the right edge where it appeared the bottom of a plate was exposed. “Let me get some more of it cleared off and make certain it’s loose.”

I brought in the water and sprayed off the plate, washing away the broken fragments. It appeared to be about 4 inches across. The sides of a couple amazonites showed so we were fairly certain there would be at least a partial plate. We hoped if there were smokies we could find them and reattach them. Our experience taught that almost without exception the smokies would be detached so we were prepared for this. I carefully raked through the rubble, pulling out any smoky quartz fragments. There were very few.

“Okay, Mike,” Tim finally said. “I think it’s loose. Here, you can pull it out. Just make sure you pull it straight out and don’t wiggle it. You’ve probably collected a ton of pockets, but I tell everyone the same thing. It’s important to remember. You don’t want to chip a tip.” He demonstrated the angle from which to pull.

Mike agreed and carefully reached into the pocket while Tim backed away.

“Hold it,” I hollered. I had nearly forgotten to get the camera. “Okay, now you can pull it, Mike.” Many times I had taped what looked like a good specimen only to have it a complete dud. No telling. You just had to take a chance and tape everything.

Like a saber being unsheathed, Mike carefully pulled out the plate and turned it over. The sound of everyone cheering told me it was good. I couldn’t see it well, trying to hold the camera steady and get a good shot.

Mike laughed, holding up the specimen in his hand, smoky quartz crystals projecting from it. “Well, maybe you can call it the Smithsonian pocket,” he said.

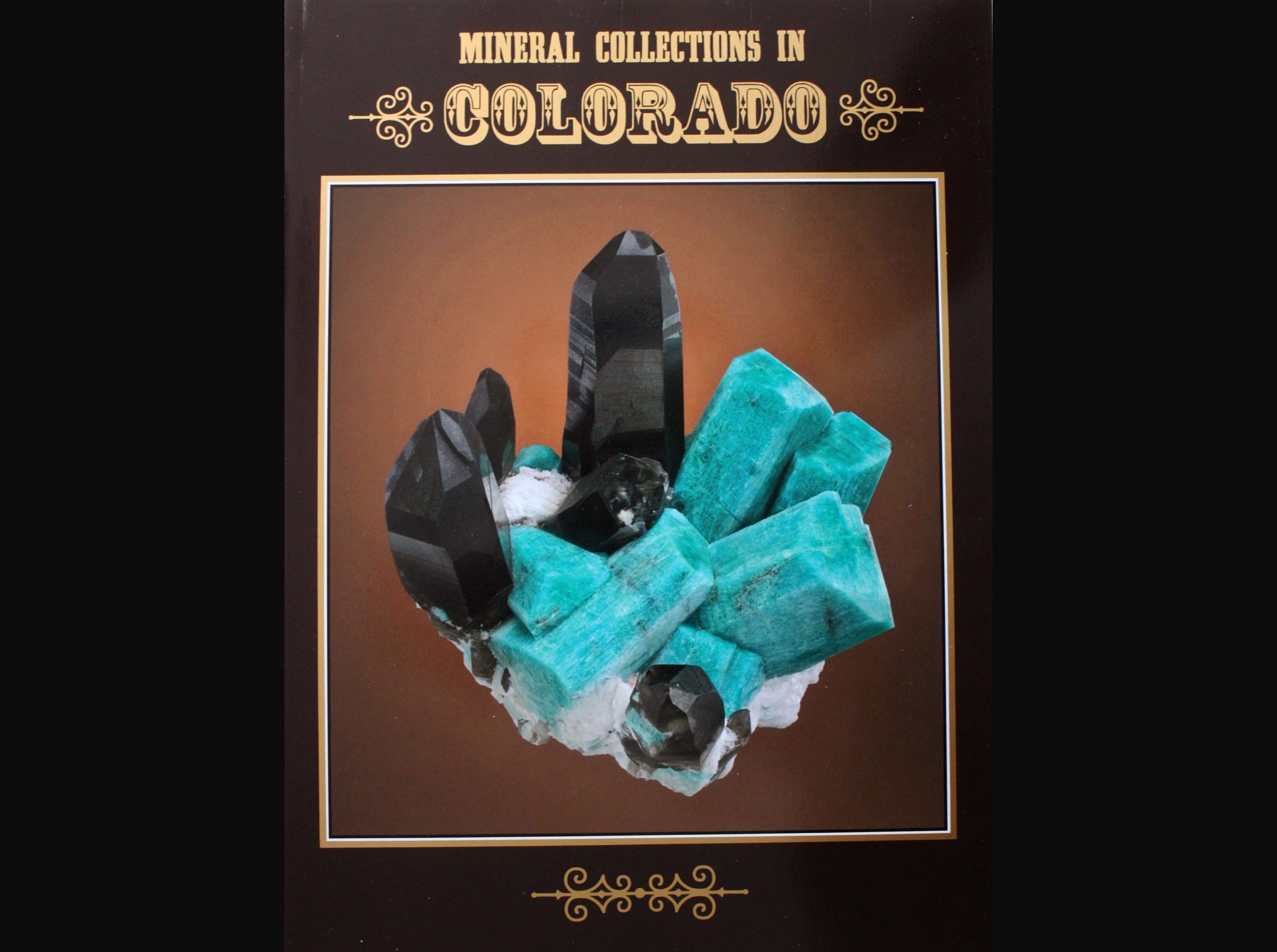

Chuck pulled over the bucket of water, took the piece, and immediately began washing. Soon, dripping wet, gleaming blue green in the sun, he presented it to the crowd of folks who had gathered around. This was an incredible plate. It showed five smokies nested amongst numerous amazonites with a ball of cleavelandite nestled amongst them. The smokies ranged up to 2.5 inches and showed, glossy black. The amazonites ranged to 1.5 inches and showed bright blue green. The plate proved to be 5 inches by 4.5 inches. It was completely intact—no damage, no missing crystals.

Mike had probably pulled out the most perfect plate found in the district to date!

We were all ecstatic. With breaths held, we watched each piece as Tim pulled them out and turned them over. We waited anxiously for the next plate. Soon, Tim pulled out a nice amazonite cluster and after washing, set it aside. He pulled out several fat smokies and then began patiently trying to fit them to the amazonite. To me it didn’t look like they would go.

“Got it,” he exclaimed happily, and held up a beautiful, long smoky now expertly fitted to some nice amazonites. Another good group!

Tim continued pulling pieces. Volunteers washed and wrapped. By the end of the day, we still had some pocket to work, but sadly had found no more plates.

With tomorrow being the Colorado Springs Mineral Show, we called it quits. I had Tim bury the pocket under 6 feet of dirt, and we closed up the site. Now I was happy I had a gate at the bottom of the hill that I could lock.

Monday 23 June 08: We had been anxious to return to the Smithsonian Pocket. Everyone at the show, naturally, had heard about it (despite me cautioning my visitors to keep quiet) and when I arrived to set up, I was met with numerous congratulations. It made me so nervous that word had gotten out that I sent Tim back out to further bury the pocket. If certain people knew I was at the show and that a good pocket had been found, they would take the opportunity to dig down through 6 feet of dirt. I didn’t want to take the chance. I almost laughed when I saw the spot on Monday morning. Tim had buried it under at least 12 feet.

Today, we had another group of visitors. Kevin Dixon and his 13-year old son Sean came by to help and watch. Four people from one of the Denver clubs had also come down to see the operation and drop off John Lowe, a high school senior who had arranged to work for us for a few days. We drilled and shot two boulders just to the right of the Smithsonian so we could cut deeper behind the pocket. Then, removing the rubble and dirt, we resumed collecting.

George and Robert did some repairs on the 992 while we collected. A hydraulic line bracket had broken and the lines were flapping loose. George and Robert welded a new plate onto the boom, securing the lines, then Robert returned to the excavation to assist.

A hose also broke under the control box on the 992, late afternoon. I made a parts run to Woodland Park while Robert opened up the gear box. Fortunately, we were able to make the repair before sundown.

We finished the Smithsonian rather quickly. Only a few single smokies and amazonites remained. However, immediately behind the Smithsonian, along the same pegmatite we hit 08-031, and afterwards, almost at the surface, another pocket, 08-032.

These pockets both contained amazonites of incredible color. Unfortuantely, 08-031 was mostly rubble. It did produce a few outstanding amazonites. We named it the Robin pocket due to the great robin-egg blue. Pocket 08-032, despite its open cavity and great looks, held nothing but rubble.

In summary, the “Smithsonian” pegmatite had five well-defined pockets along its length and a couple areas that bulged out and produced a few singles. The pegmatite ran a length of about 25 feet from surface to excavation floor before it petered out into a few marginal stringers.

By day’s close, the material from the Smithsonian pocket filled 16, 4-inch deep flats.

Thunderstorms rolled in during the late afternoon. It was good to finally get a bit of moisture, albeit, the sky was pretty wicked. I worried Chuck and I might need to spend the night in the car, but the clouds eventually moved away. It was then a beautiful evening—golden light angled across the pines on the northern ridges. It was a great evening with Chuck and Baxter on Smoky Hawk mountain.

Since discovering the Smithsonian pocket 19 June, we’ve washed the pieces and laid it out for assembly. It fills three, 6-foot tables, one card table, two TV trays, and part of another shelf.

Here are some photos of the small boxes containing the pieces and the assembled plates. The pocket is laid out from left to right, top of table to bottom, in the order in which the pieces were collected. This gives us a better chance of finding missing fits, although many times, pieces are hopelessly mingled.

We plan to have the Smithsonian available at the fall Denver Show, in our room, Room 182, Holiday Inn.

A few of the finished groups. We recovered about six groups and lots on nice single amazonite crystals.